Apple's Problem with Bodies

Building for iOS sometimes feels like archaeology: brush away enough guidelines and you hit something older and stranger. A system that can classify violence with forensic precision still can't decide if the human body is health, lifestyle, or sin.

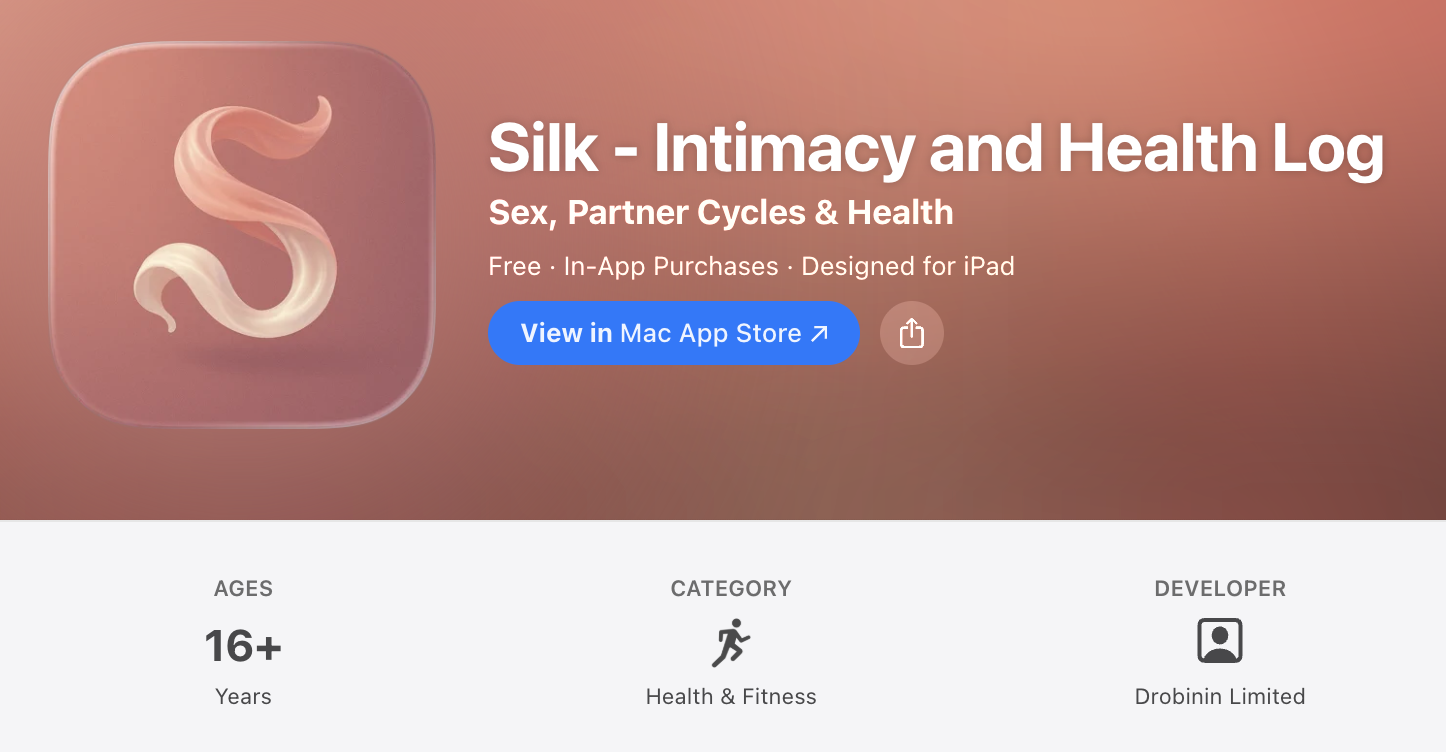

One day I tried to ship a private intimacy tracker–nothing scandalous, just a journal for wellbeing–and App Store Connect assigned it the 16+ rating it uses for gambling apps and "unrestricted web access". The rating itself is fine: the target audience is well past that age anyway. What baffles me is the logic.

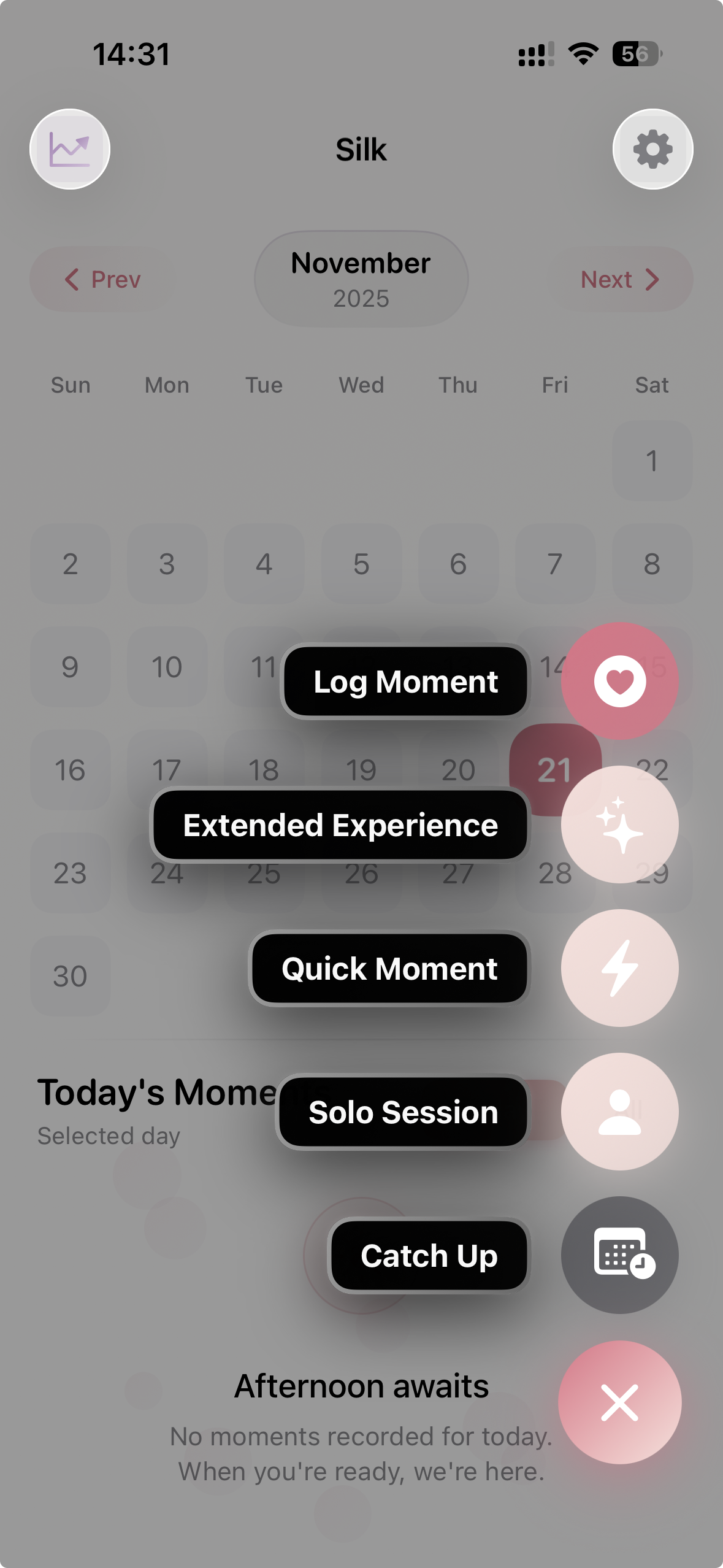

Silk–the app I’m talking about, almost reluctantly–is a wellbeing journal in the most boring sense possible. You choose a few words about your day, moods, closeness, symptoms, or whatever else matters to you and your partner(s). It lives entirely on-device, syncs with nothing and phones no one. The whole point is that nothing interesting happens to your data after you close the app.

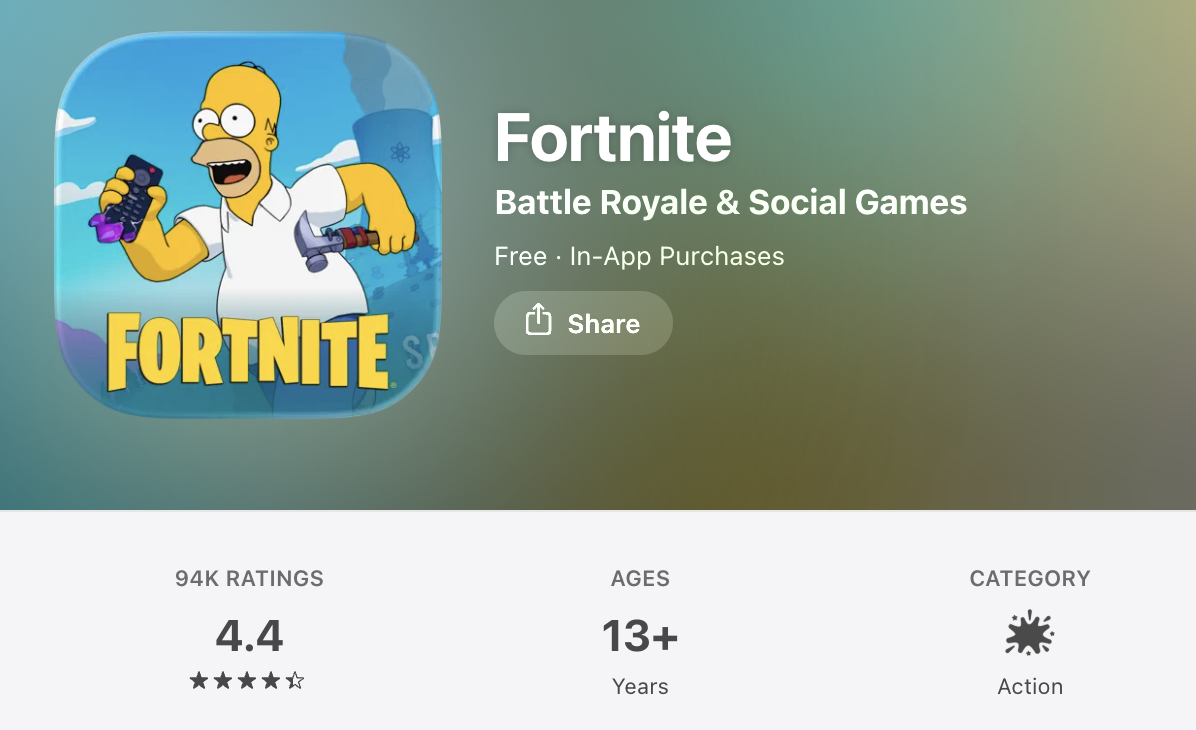

And yet, from the App Store’s point of view, you can build a game with guns and cartoon violence and happily ship it to kids, while a private wellbeing journal gets a 16+ label. The label isn’t the problem, the problem is that it’s doing the job of an entire missing category.

If you build something about bodies that isn’t medical, reproductive, or dating-adjacent, the App Store doesn’t quite know where to put it and reaches for the only bucket available.

Welcome to the grey zone.

A Category With No Name ¶

If you were around for the early App Store, you’ll remember its optimism: accelerometer-driven beer glasses, wobbling jelly icons, flashlight apps that set brightness to 100% because no one had ever considered the idea before. The ecosystem assumed “content” meant pictures, sound, or the occasional cow-milking simulator–not a user quietly describing part of their life to themselves.

The App Store still carries the outline of that first life. Its vocabulary came from iTunes, which came from film ratings, built for a world where "content" meant something you could point a camera at. When the App Store arrived in 2008, it reused that system because it was available–and because no one expected apps to do much beyond wobbling or making noise.

Those assumptions didn’t last. By 2009 the Store had hosted an infamous $999 app that did nothing but display a red gem, a game where you shook a crying baby until it died, and enough fart apps that one reportedly earned five figures daily[1]. The review process was learning in public.

Against that backdrop, Apple introduced age ratings in mid-2009 with iOS 3. The strictest category, 17+, wasn't really created for gore or gambling–it was a pressure valve for novelty apps where shaking your phone made cartoon clothes fall off. Anything that might show “objectionable content”, from bikini galleries to embedded browsers, went into the same bucket[2].

Change of Direction ¶

By 2010, Apple reversed course. After Steve Jobs declared "folks who want porn can buy an Android phone," thousands of sexy-but-not-explicit apps vanished overnight in what became known as the Great App Purge[3]. The platform moved from reactive cleanup to something more systematic.

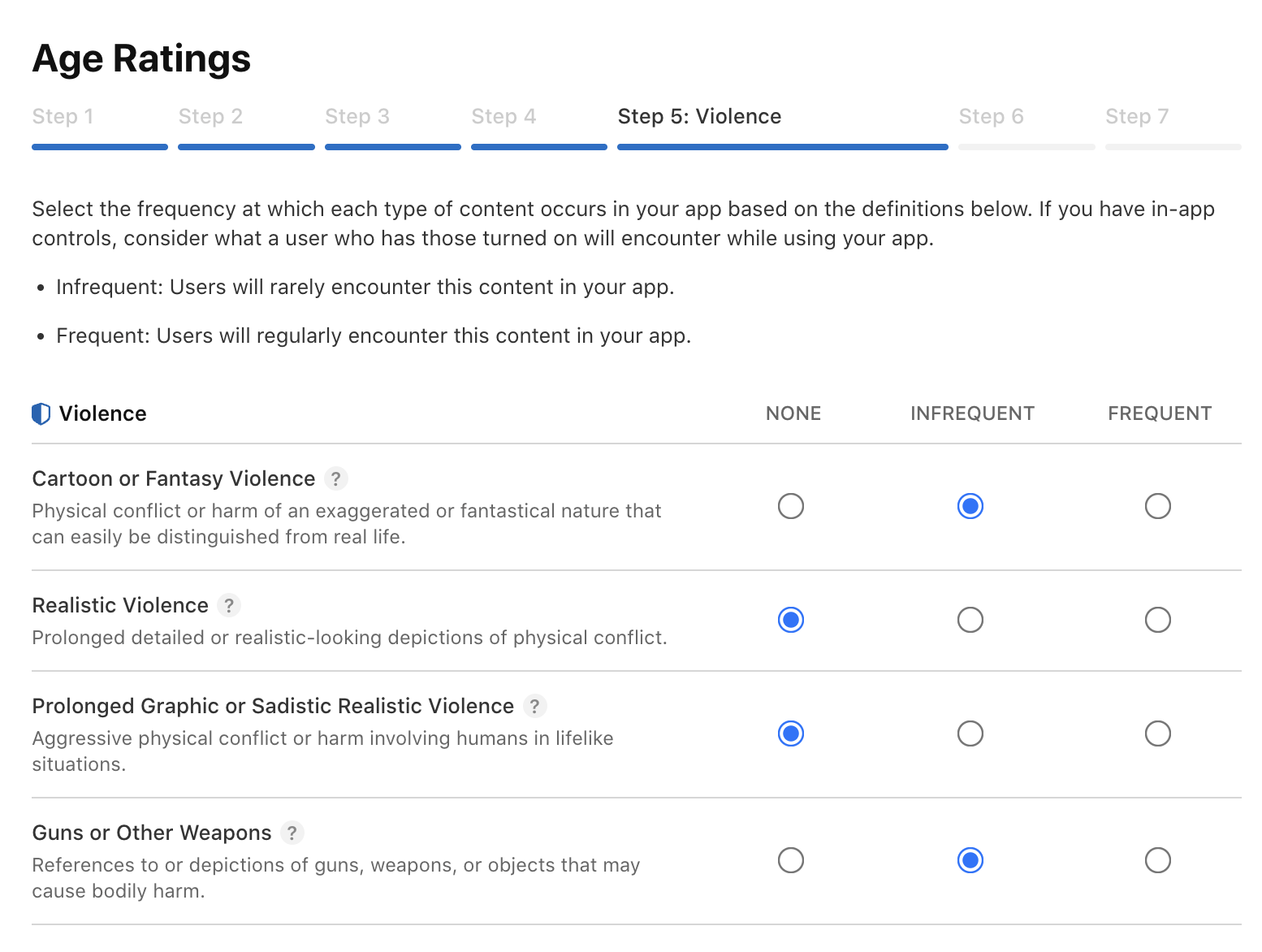

The Age Ratings matrix Apple operates now in iOS 26 is far more precise. It defines violence with forensic granularity, subdivides gambling, categorises medical risk. It does all the things a global marketplace must do once everyone realises software can cause harm.

But the matrix still retains its original silhouette: everything is defined by "content," not context. App Review's logic is keyed to artifacts inside the bundle–screenshots, metadata, stored assets–not to what the software actually does. That works beautifully for games and media. It falls apart when the "content" is whatever the user decides to write that day.

Silk has no images, no user-generated photos, no feed, no external links. The matrix rated it 16+ anyway–the same tier as gambling apps and unrestricted browsers. The rating isn't describing what Silk does. It's describing the absence of a category that should exist.

What about Apple Health? ¶

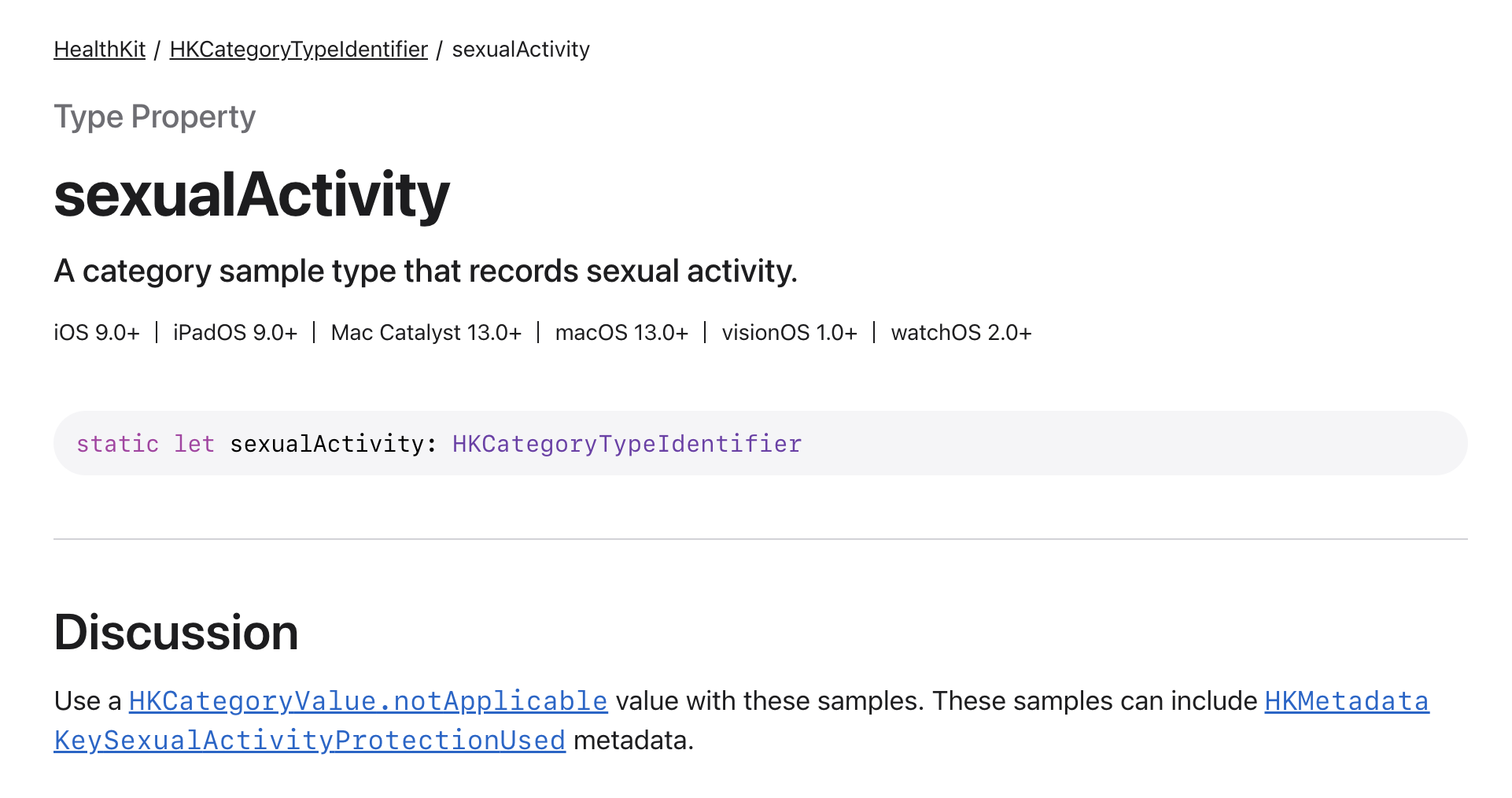

When HealthKit launched in 2014, Apple consciously avoided anything resembling "behavioural interpretation." Heart rate or steps were fine, relationships were not. A decade later, the API surface has expanded in every direction–sleep depth, sound exposure, handwashing, environmental allergens, even a "Sexual Activity" field added quietly in iOS 9[4]. But relational wellbeing remains conspicuously absent.

HealthKit tracks heart rate, inhaler usage, mindfulness minutes, and the more delicate end of gastrointestinal bookkeeping. Nowhere does it model intimacy, affection, or closeness–the things couples might actually want to track privately. If the platform doesn't have words for what you're building, the classification system can't label it correctly. The vocabulary doesn't exist.

Apple is not avoiding the topic here, they’re being literal. And when a system is literal in a domain that is inherently contextual, things start to get interesting.

Blind Spots Mean Constraints ¶

The first place that breaks is search.

Apple's search infrastructure is fast and strict. Search for "budget app" and you get budget apps. Search for "meditation" and you get meditation apps plus a few over-confident habit trackers. Search for the phrases people actually use when they want what Silk does–"relationship journal", "couples diary", "private moments"–and you get wedding planners, travel blogs, generic note-taking apps, and the occasional CBT worksheet. The algorithm can't read between lines it doesn't know exist.

The Metadata Minefield ¶

On the developer side, metadata stops being about discoverability and becomes a small diplomatic exercise. A few terms trigger moderation, a few trigger follow-up questions, and the keyword field turns into a minefield where every word is inspected for what it might imply rather than what it means. Too specific reads like medicine, too gentle reads like romance, and anything metaphorical gets outright rejected.

This isn't new though. In 2009, Ninjawords–a perfectly useful English dictionary–was delayed and forced into 17+ because it could return definitions for swear words[5]. Phil Schiller personally explained that since parental controls promised to filter profanity, any app displaying unfiltered words needed age-gating. Never mind that Safari could look up far worse. The rule was simple: uncurated content equals adult content, context be damned.

There's also the "massage" rule, mostly folklorfe but widely believed: any app with that word in its metadata triggers extended review, whether it’s physiotherapy or post-marathon recovery. The system was burned once by apps using "massage" as euphemism and never forgot. Most of the odd heuristics you encounter today are scars from 2009.

Ambiguity in meaning becomes ambiguity in engineering. Without shared vocabulary, misalignment cascades: classification shapes search, search shapes metadata, metadata triggers review flags. The policies update faster than the taxonomy beneath them evolves.

Once you see that, the problem becomes solvable–not culturally, but technically.

Time to Poke the System ¶

At this point I did the only sensible thing: treated App Store Connect like a black box and started running experiments.

First test: keywords using only soft language–"relationship journal", "partner log", "connection tracker". Search rankings tanked. Silk dropped to page 8 for "relationship journal," outdone by printable worksheets for couples therapy. Good news: the algorithm was confident I wasn't selling anything objectionable. Bad news: it was equally confident I wasn't selling anything at all.

Replacing those with direct terms–"intimacy tracker", "sexual wellness", "couples health"–brought visibility back to page 2–3. It also triggered longer App Review cycles and required increasingly elaborate "Review Notes" explaining why the app shouldn't be rated 18+. Same binary, screenshots, and code, but different words in a metadata field neither the users nor I can even see in the UI.

Screenshots followed the same logic. Completely sterile set–empty fields, no microcopy, generic UI–sailed through but made Silk look like Notes with a different background. A more honest set showing what the app actually does triggered the 18+ question again. The framing changed the classification. The classification changed nothing about what the software does, but everything about where it appears and who finds it.

None of this is surprising if you assume the system is a classifier trained on categories from 2009. From the outside it feels arbitrary. From the inside it's doing exactly what it was built to do: match patterns it understands and escalate the ones it doesn’t. It just doesn't have a pattern for "private health journal that mentions bodies", even though there are lots of private health journals in the App Store these days. You can almost hear it thinking: This smells like health but reads like dating and contains the word 'intimacy.' Escalate!

Designing Around the Gap ¶

Silk’s architecture was shaped by this lag in the same way Fermento’s safety checks were shaped by gaps in food-safety guidance, or Residency’s "compiler warnings" for travel emerged from inconsistent definitions of “presence” by different countries. It’s not a case study in “growth”; it’s just another example of what happens when you have to reverse-engineer the missing assumptions. When a domain refuses to state its rules, you provide the scaffolding yourself.

Most of the engineering time went into figuring out what not to build–not from fear of rejection, but from understanding how classifiers behave when they encounter undefined cases. Treat it like a compiler that hasn't learned your edge-case syntax yet and stay inside the subset of language it already understands. The discipline felt familiar–the same kind you develop when building in domains where the platform's rules aren't fully specified and you have to infer the boundaries from failed experiments.

The more carefully you specify what the app does, the less the platform has to guess on your behalf. In 2010, you could ship "Mood Scanner" apps that claimed to read emotional states from fingerprints. They still exist–the App Store didn't purge them–but try submitting one in a category App Review associates with actual health data and you'll trigger very different questions. The scrutiny isn't random; it’s contextual. It depends on how your metadata accidentally pattern-matches against old problems.

Life in the Grey Zone ¶

The closer Silk came to shipping, the more I understood the App Store's behaviour as conservatism–not ideological, but technical. The kind that keeps a global marketplace from accidentally approving malware. Some of this conservatism is regional: China's App Store has additional filters for "relationship content," South Korea requires separate disclosures for wellbeing data. Apple unifies this under one policy umbrella, which produces a system that's cautiously consistent across borders but not particularly imaginative about edge cases.

The post-Epic world made Apple more explicit about where liability lives. Ambiguity became expensive, underspecification became expensive, classifiers that behave "roughly right" became expensive. The safest rule became simple: if the system can't clearly state what something is, err on caution until the taxonomy expands.

The cost is that new categories appear slowly. Sleep apps lived on the periphery for years. Meditation apps bounced between "Health" and "Lifestyle" depending on screenshot aesthetics. Third-party cycle trackers existed for nearly a decade before Apple added native reproductive health tracking in 2015 and a dedicated Cycle Tracking experience in 2019[6]. Digital wellbeing apps faced suspicion until Screen Time shipped in iOS 12. Each category began as an edge case, proved itself through user adoption, and eventually got formalized–usually announced in a single sentence at WWDC as if it had always existed.

Silk is at the beginning of that cycle. Eventually Apple will introduce a more nuanced descriptor, or HealthKit will model relational wellbeing, or the age matrix will gain more precision. The entire ecosystem will re-index overnight and everyone will move on.

It turns out the best way to handle a category that doesn’t exist is to build as if it does, then wait for the taxonomy to catch up. Until then, the grey zone is honestly not a bad neighbourhood. The users already know what the app is for. The platform will figure it out eventually.

Working in the quiet gaps of the platform? I build iOS software for the problems people don't talk about. Hire me →

I Am Rich sold for $999.99 to eight people before Apple quietly yanked it. Baby Shaker made it through review until the backlash arrived. And iFart really did clear ~$10k/day at its peak. ↩︎

The 17+ category arrived with iOS 3 in 2009. Officially it covered “mature themes” and gambling. Unofficially it was the overflow bin for anything vaguely sexy–from Wobble iBoobs to apps with embedded browsers, RSS readers, and Twitter clients, all lumped together because they might show something naughty. ↩︎

The 2010 “Great App Purge”: 5–6k sexy-but-not-explicit apps disappeared overnight after Steve Jobs dropped the immortal “Folks who want porn can buy an Android phone.” A rare moment where Apple said the quiet part out loud. ↩︎

HealthKit launched in iOS 8 with vitals and fitness but no reproductive health. Apple added “Sexual Activity” in iOS 9–a year after everyone noticed the omission. ↩︎

Ninjawords, a dictionary, was rated 17+ because it could return swear words. Behold: a dictionary rated like a strip-poker app, because it contained words the app reviewers searched for on purpose. ↩︎

Third-party cycle trackers existed for years, but Apple didn’t add reproductive health metrics until iOS 9 (2015), and didn’t ship dedicated Cycle Tracking until iOS 13 (2019). A category legitimised years after users created it. ↩︎